The St. Regis Chicago’s grand ballroom glittered with crystal chandeliers, polished marble floors, and guests dressed in couture gowns and tailored tuxedos. The event was an extravagant engagement party celebrating Jonathan, the golden son of the family, and his fiancée Elise, whose entrance into Chicago’s elite cemented the union of two powerful families. Yet amid the shimmer of champagne flutes, Ecuadorian roses, and the self-congratulating pride of parents and relatives, one figure existed quietly at the margins: Jonathan’s sister.

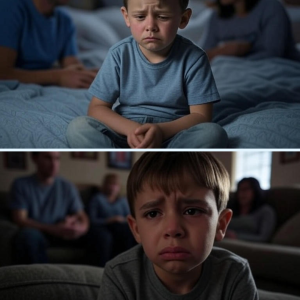

The narrator’s experience of the evening offers a poignant lens through which themes of class, invisibility, and family favoritism emerge. While her brother basks in admiration and privilege, she blends into the edges of the ballroom, dressed in a modest navy sheath and discount flats.

Guests mistake her for a server, and even her mother calls her across the room to fetch canapés for Elise’s parents, treating her less like family and more like hired help. This moment is not an isolated humiliation but rather the culmination of years of living in Jonathan’s shadow.

Jonathan’s life has been carefully curated for success: a scholarship to Wharton, the youngest vice president at his firm, and a fairytale romance with Elise that will soon be immortalized in glossy magazines. His confidence radiates, and his parents beam with pride as they recount his achievements. By contrast, the narrator remains unnamed, her presence reduced to silence, service, and invisibility. She is not celebrated for her individuality but diminished to a “family footnote,” a reminder of the unspoken hierarchy within the household.

The grandeur of the party also highlights the stark contrasts of social class. While Elise’s parents, Charles and Margaret Wentworth, embody old Chicago wealth with its understated elegance and inherited prestige, the narrator is more aligned with the staff than the guests. She feels more comfortable helping the catering team than engaging in conversations about hedge funds, ski chalets, and Ivy League acceptances. This juxtaposition underscores the alienation of those who lack wealth or status in environments obsessed with social capital.

Ultimately, the engagement party is less about love than it is about spectacle and performance. The roses, the jazz quartet, and the imported champagne are not symbols of intimacy but of display—markers of a union meant to be admired, envied, and published. The narrator’s outsider perspective strips away the glamour, exposing the emotional cost of living in the shadow of someone else’s perfection.

In this story, the chandeliers may cast shimmering rainbows, but they also illuminate a painful truth: that within families and societies alike, worth is too often measured by wealth, achievement, and appearances. And in such spaces, those who do not fit the mold—those who lack the sheen of success—become invisible, their voices muted in rooms full of chandeliers.